Kunmes

A sumér zodiákus Halak jegynek megfelelő neve Kun-Mes. A nyelvészek Farkak jelentéssel adatolják ezt a csillagképet, minthogy Kun (ahogy kûn, KONY és konyec szavaknál is láttuk) farkat, a ló farkát (vagy ékalakú pofáját) jelenti, Mes pedig a többesszámot(?). MES Péterfai Jánosnál Ifjú, Hős jelentésű, de MISZ-hez, mézhez is köthető lehet. MES címnél legutóbb alternatív levezetése is született Kunmes-nek: MES a mes-fa, a messzi fa, a Világfa, a Tejút neve és ennek alsó vaskori ideje a Halak (mikor is a tavaszpont[1] a Halakba ér).

Gavin White Babylonian Star Lore...

...című könyvében ír róla:

- A "Great One" fordításában Gula nevétadom, mert a szakirodalom tévesen GAL = Nagy (Ő) értelemben veszi.

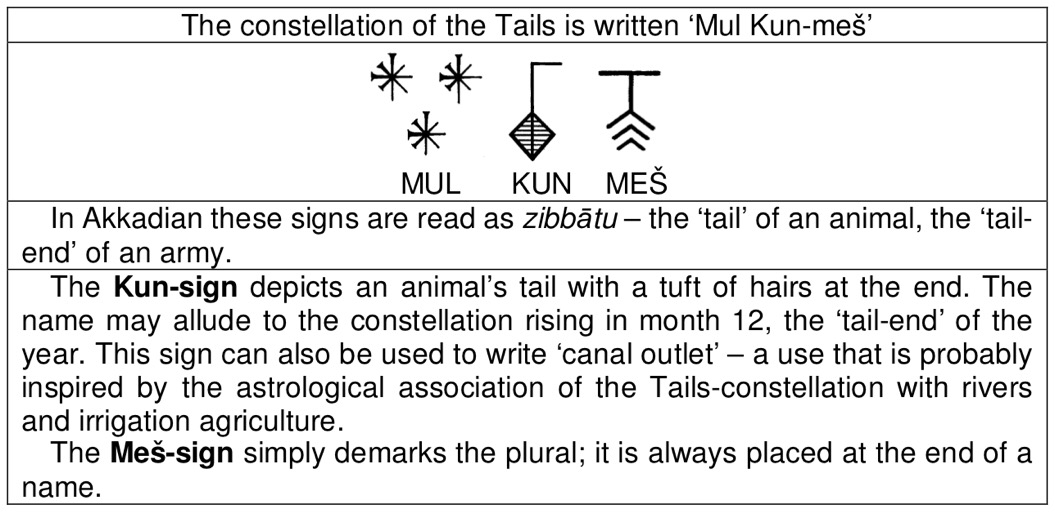

THE TAILS

The origins of Pisces as a pair of fish can be traced back to the Babylonian constellation called the Tails. Even the concept of the cord or ribbon that joins the two fish together can be found in late Babylonian star-lore, where the 'bright star of the ribbon of the Fishes' is regarded as the lead star of the so-called 'Normal stars' – a series of 32 stars located close to the ecliptic that are used as reference points for locating the planets. The cord itself is doubtless another example of a celestial bond that often appears in Babylonian star-lore in connection with the location of the solstices and equinoxes – the points in the solar year that are figuratively 'fixed' in relation to the stars.

There is every reason to believe that the idea of the cord would only have been applied to these stars in the latter half of the 1st millennium when they came to mark the position of the spring equinox. Before this time the two component parts of the cord would have been envisioned as the two great rivers of Mesopotamia, the Tigris and Euphrates. The origin of the 'knot' that unites the two cords represents the Shat-al-Arab where the two great rivers join together before flowing into the Gulf of Bahrain.

This image of the two rivers is the ultimate origin of the symbolism of Pisces – as rivers are typically represented in Babylonian art as a pair of wavy lines with tiny fishes added along their courses to further emphasise their watery nature (see fig 2). The whole image is copied from nature as the 12th month of the year, which is marked by the rising of the Tails, is the season that river carp swim upstream to their breeding grounds in rivers swollen by melt waters from the mountains.

As the basic economy of Mesopotamia was founded on irrigation agriculture, the floodwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates were essential to the ongoing prosperity of the land. The Tails can thus be seen to form an integral part of the farming symbolism centred on the nearby constellation of the Field. When the Tails are favourably aspected they are thought to predict good floods: 'If the Wild Sheep approaches the Tigris-star: there will be rain and flood'; and an abundant flood naturally brings a plenteous harvest in its train: 'If Jupiter stands in the Tails: the Tigris and Euphrates will be filled with silt; there will be prosperity and abundance in the land'.

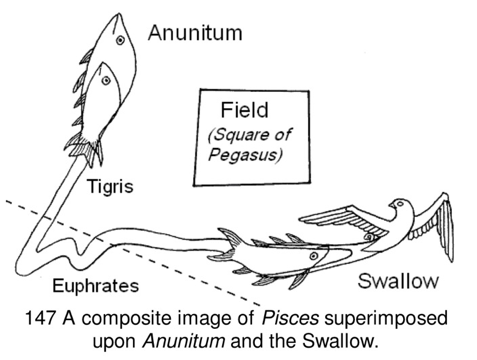

The constellation of the Tails first appears among the 'stars on the path of the Moon', a series of 16 ecliptic constellations listed in Mul-Apin that are the Babylonian forerunner of the 12 zodiac constellations. The asterism itself gives the impression of being a newly formed figure specifically designed to represent the 12th month of the year. As its full name reveals – 'the Tails of Anunitum and the Swallow' – the Tails is really a composite constellation, made up from the parts of other pre-existing star figures. The name only becomes understandable in light of the illustration (fig 147 above) that superimposes the modern image of Pisces upon the corresponding Babylonian constellations. It shows that the Piscean fish are considerably smaller than their Babylonian counterparts – and that only the tails of the respective constellations actually correspond to each other.—

A FAROK

A Halak, mint halpár eredete a Babiloni csillagképre vezethető vissza, amelyet Faroknak neveztek. Még a két halat összekötő zsinór vagy szalag fogalma is megtalálható a késő babiloni csillagászatban, ahol a "Halak szalagjának fényes csillagát" az úgynevezett "Normálcsillagok" vezető csillagának tekintik - egy 32 csillagból álló, az ekliptika közelében elhelyezkedő sorozatnak, amelyet a bolygók helymeghatározásához referenciapontként használnak. Maga a zsinór kétségtelenül egy másik példája annak az égi köteléknek, amely a babiloni csillagászatban gyakran megjelenik a napfordulók és napéjegyenlőségek - a napév azon pontjai, amelyek képletesen "rögzítettek" a csillagokhoz viszonyítva - elhelyezkedésével kapcsolatban.

Minden okunk megvan azt hinni, hogy a zsinór gondolatát csak az 1. évezred második felében alkalmazták ezekre a csillagokra, amikor a tavaszi napéjegyenlőség helyét jelölték. Ezt megelőzően a zsinór két alkotóelemét Mezopotámia két nagy folyójának, a Tigrisnek és az Eufrátesznek képzelték el. A két zsinórt egyesítő "csomó" eredete a Shat-al-Arabot jelképezi, ahol a két nagy folyó egyesül, mielőtt a Bahreini-öbölbe ömlene.

Ez a két folyó képe a Halak szimbolikájának végső eredete - mivel a folyókat a babilóniai művészetben jellemzően hullámos vonalak párjaként ábrázolták, amelyek mentén apró halakat helyeztek el, hogy tovább hangsúlyozzák vizes jellegüket (lásd a 2. ábrát). Az egész képet a természetből másolták, mivel az év 12. hónapja, amelyet a Farkasok felkelése jelöl, az az évszak, amikor a folyami pontyok a hegyek olvadékvizei által felduzzasztott folyókban úsznak felfelé a szaporodóhelyeikre.

Mivel Mezopotámia alapvető gazdasága az öntözéses mezőgazdaságon alapult, a Tigris és az Eufrátesz árvizei nélkülözhetetlenek voltak az ország folyamatos jólétéhez. A Farkak így a közeli Mező csillagképre összpontosító mezőgazdasági szimbolika szerves részének tekinthetők. Ha a Farok kedvező fényszögben áll, akkor jó árvizeket jósolnak: "Ha a Vadjuh megközelíti a Tigris-csillagot: eső és áradás lesz"; és a bőséges áradás természetesen bőséges termést hoz magával: "Ha a Jupiter a Farokban áll: a Tigris és az Eufrátesz megtelik iszappal; jólét és bőség lesz a földön".

A Farok csillagkép először a "Hold útjának csillagai" között jelenik meg, a Mul-Apinban felsorolt 16 ekliptikus csillagkép között, amelyek a 12 állatövi csillagkép babiloni előfutárai. Maga a csillagkép olyan benyomást kelt, mintha egy újonnan kialakított alakzat lenne, amelyet kifejezetten az év 12. hónapjának jelölésére terveztek. Amint azt teljes neve is elárulja - "az Anunitum és a Fecske farka" -, a Farok valójában egy összetett csillagkép, amelyet más, már korábban létező csillagképek részeiből állítottak össze. A név csak a fenti illusztráció (147. ábra) fényében válik érthetővé, amely a Halak modern képét helyezi a megfelelő babiloni csillagképekre. Ebből kitűnik, hogy a Halak halai lényegesen kisebbek, mint babiloni társaik - és hogy a megfelelő csillagképeknek valójában csak a farkuk felel meg egymásnak.

Gavin White könyvének interneten elérhető kivonataiban tallózva az előző jegy a Vízöntő Gula, a következő jegy pedig a Kos/Béres Luhunga.

Lábjegyzetek

Lábjegyzet:

Úgy tűnik, valóban a tavaszpont bizonyos jegybe érése adja meg az egyes jeltartományok neveinek értelmét. Erre a Halak – Halál – Kali Yuga korszaka jó bizonyíték. ↩︎