Allul

A sumér zodiákusban a Rák jegynek megfelelő jegy, helyesen Al-Lul felbontásban.

A mellékelt ábra és szöveg...

Gavin White Babylonian Star Lore...

...című könyvéből származik:

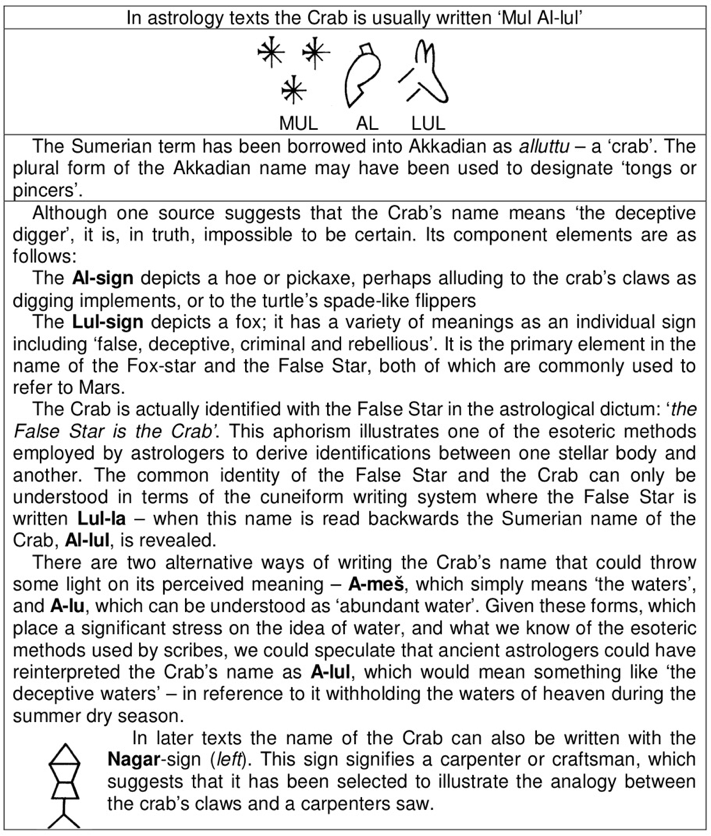

In astrology texts the Crab is usually written 'Mul Al-lul'

The Sumerian term has been borrowed into Akkadian asalluttu- a 'crab'. The plural form of the Akkadian name may have been used to designate 'tongs or pincers'.

Although one source suggests that the Crab's name means 'the deceptive digger', it is, in truth, impossible to be certain. Its component elements are as follows:

The Al-sign depicts a hoe or pickaxe, perhaps alluding to the crab's claws as digging implements, or to the turtle's spade-like flippers.

The Lul-sign depicts a fox; it has a variety of meanings as an individual sign including 'false, deceptive, criminal and rebellious'. It is the primary element in the name of the Fox-star and the False Star, both of which are commonly used to refer to Mars.

The Crab is actually identified with the False Star in the astrological dictum: 'the False Star is the Crab'. This aphorism illustrates one of the esoteric methods employed by astrologers to derive identifications between one stellar body and another. The common identity of the False Star and the Crab can only be understood in terms of the cuneiform writing system where the False Star is written Lul-la – when this name is read backwards the Sumerian name of the Crab, Al-lul, is revealed.

There are two alternative ways of writing the Crab's name that could throw some light on its perceived meaning – A-meš, which simply means 'the waters', and A-lu, which can be understood as 'abundant water'. Given these forms, which place a significant stress on the idea of water, and what we know of the esoteric methods used by scribes, we could speculate that ancient astrologers could have reinterpreted the Crab's name as A-lul, which would mean something like the deceptive waters' – in reference to it withholding the waters of heaven during the summer dry season.

In later texts the name of the Crab can also be written with the Nagar-sign (left). This sign signifies a carpenter or craftsman, which suggests that it has been selected to illustrate the analogy between the crab's claws and a carpenters saw.

—

Az asztrológiai szövegekben a Rákot általában 'Mul Al-lul'-nak írják.

A sumér kifejezés az akkád nyelvbealluttu– "rák" – néven került át. Az akkád név többes számú alakját talán 'fogó vagy fogó' megjelölésére használták.

Bár az egyik forrás szerint a Rák neve azt jelenti, hogy 'a csaló ásó', valójában lehetetlen biztosat mondani. Az alkotóelemei a következők:

Az Al-jel egy kapát vagy csákányt ábrázol, talán utalva a rák karmaira, mint ásóeszközökre, vagy a teknős lapátszerű uszonyaira.

A Lul-jel egy rókát ábrázol; egyéni jelként számos jelentése van, többek között "hamis, csaló, bűnöző és lázadó". Ez az elsődleges eleme a Róka-csillag és a Hamis csillag nevének, mindkettőt általában a Marsra vonatkoztatva használják.

A Rákot valójában a Hamis csillaggal azonosítják az asztrológiai mondásban: "a Hamis csillag a Rák". Ez az aforizma az asztrológusok által alkalmazott ezoterikus módszerek egyikét szemlélteti, amelyekkel az egyik és a másik égitest közötti azonosításokat vezetik le. A Hamis Csillag és a Rák közös azonossága csak az ékírás alapján érthető meg, ahol a Hamis Csillagot Lul-la-nak írják – ha ezt a nevet visszafelé olvassuk, a Rák sumér neve, Al-lul, tárul fel.

A Rák nevének két alternatív írásmódja is van, amelyek némi fényt vethetnek a Rák vélt jelentésére: A-meš, ami egyszerűen 'a vizek', és A-lu, ami 'bőséges vízként' értelmezhető. Tekintettel ezekre a formákra, amelyek jelentős hangsúlyt fektetnek a víz gondolatára, és arra, amit az írástudók által használt ezoterikus módszerekről tudunk, feltételezhetjük, hogy az ókori asztrológusok átértelmezhették a Rák nevét A-lul-nak, ami valami olyasmit jelentene, mint a "megtévesztő vizek" – utalva arra, hogy a nyári száraz évszakban visszatartja az ég vizeit.

Későbbi szövegekben a Rák neve a Nagar-jellel (balra) írott. Ez a jel ácsot vagy mesterembert jelent, ami arra utal, hogy a rák karmai és az ácsfűrész közötti analógia illusztrálására választották.

Több szempont alapján is vizsgálja a nevet és még a szómegfordítás is szóba kerül. Az kétségtelen, hogy a rák jellemző hátrafelé végzett mozgására nem térhetett itt ki, holott azt tudnunk kell, hogy a Rákkal, azaz a június 21. körüli napfordulóval indul meg lefelé a Nap: nemcsak a napok hossza kezd csökkenni, de az égen elfoglalt helye is lejjebb lesz.

Ennek folytán okszerűnek tekinthető az alul szavunkra bökni, és az akkád alluttu nyomán akár halott szavunkra is, és itt érdekes kitérni Ullu névvel való hasonlóságára is, mellyel kapcsolatban írja – Badiny Jós Ferenc nyomán – Vetráb József Kadocsa:

Azt a napot, amelyen a leghosszabb ideig süt a Nap, és amelyiken legrövidebb az éjszaka, Ullunak hívták.

- Ez mai fejjel június 21, de mindenképpen a nyári napforduló. Ellenpárja a Turul, Vetráb szerint.

Mindez tökéletesen összevág a Bak-Rák tengelynél írottakkal.

Gavin White Babylonian Star Lore című könyvének további adatai kerülnek bemutatásra:

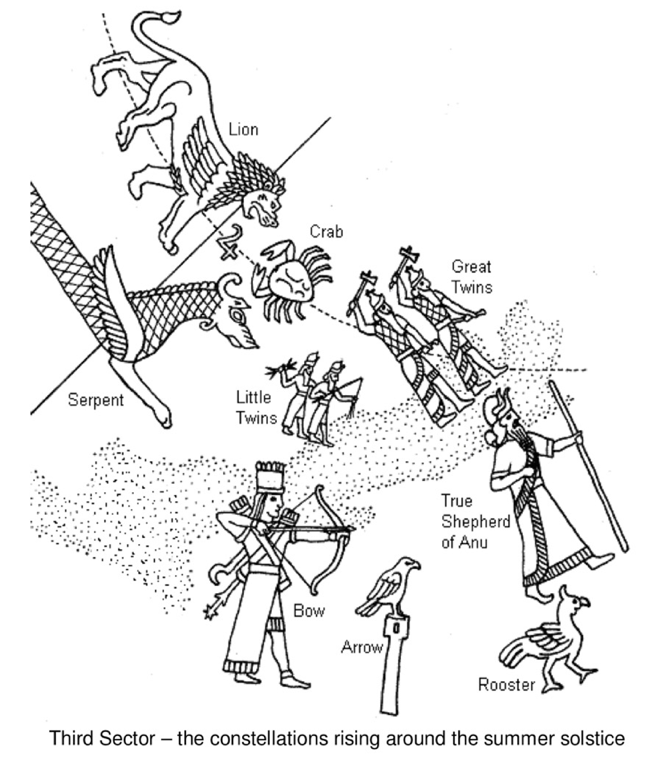

THE SUMMER SOLSTICE PERIOD

The next distinct group of symbols is made up from the constellations that rise during the summer. These stars mark the hot dry season, which, unlike the milder climes of Europe, is regarded as the time of death in Mesopotamia. At this time the lands are ravished by drought and plague, and even nature herself becomes barren – the life-giving rains have ceased and river levels decline, the harvest is finished and all vegetation dies back under the scorching summer sun.

As the sun approached the peak of his powers, Dumuzi had foreboding dreams of his own death. His premonitions came true at the summer solstice and his funeral rites were performed amidst wailings and lamentations in month 4, immediately after the solstice. As Dumuzi walked the path of the dead, he took the sorrows of the worlds with him to the land of the shades.

Rituals dedicated to the dead also dominated month 5, which fell in late summer. At this time, when the veil between life and death was at its thinnest, the great Brazier festival was celebrated. This festival commemorated the ancestors, who were invited back to the world of the living for an annual feast in their descendant's homes. The rites involved lighting torches and braziers to guide the departed ghosts of the ancestors back from the darkness of the underworld. The stars rising around the time of the summer solstice are thus fittingly informed by images of death, war and travel between the worlds.The Serpent is one of the primary symbols of death and the underworld. Like its Greek counterpart, the Hydra, the Babylonian Serpent was set in the heavens to guard an entrance to the underworld. This entrance was used by Dumuzi on his way to the underworld and it would also be the most logical route used by the ancestral ghosts when they returned to earth for the great ancestral festival celebrated in late summer. In Babylonian tradition the Serpent was held sacred to Ningišzida, the 'Lord of the Underworld' and when Death itself was envisioned it was thought to have the face of a serpent. The malign nature of the Serpent constellation is all too apparent in astrology omens where its appearance predicts famine, plague and pestilence. It is also possible that the Serpent performs a secondary seasonal role as a symbol of the summertime drought. The clearest expression of this function can be found in Greek myth where the Serpent's counterpart, called the Hydra, is literally known as the 'water-serpent'. In Greek myth the Hydra was portrayed constraining the underground waters and thereby causing springs to dry up and river levels to fall.

The Crab was also closely associated with an entrance to the underworld in Greek and Roman traditions. Much the same is implied in Babylonian traditions where some magical texts even speak of using the influence of the Crab in rites designed to raise ghosts from the underworld and to make offerings to the dead. In the section on the Crab I propose that it has ultimately inherited these otherworldly traits, as well as its strong associations to rivers, from the older constellation of the Serpent.

The underworld themes continue in the form of the Great Twins and their lesser counterparts, the Little Twins, who are all are depicted on the star-map as fully armed warriors. The Great Twins in particular, are both closely associated with Nergal, the king of the underworld, and one of them is known to travel back and forth between the realms of the dead and the upper worlds. The symbolic function of the Great Twins within the stellar calendar was to guard the summertime entranceway to the realm of the dead that was located in the region of the Serpent and Crab.

The theme of travelling between the worlds continues in the lore of the True Shepherd of Anu and his accompanying animal symbol, the Rooster, who both represent the herald of the gods. Their divinely ordained role was to communicate the messages of the gods to the denizens of every realm, which necessitated their journeying between the worlds. Among the messages they relayed would have been the decision of the gods concerning the fate of Dumuzi and the other dying gods who are now making their way towards the underworld. As 'the one struck down by a mace', the True Shepherd has himself walked the long path of the dead.

The summer solstice itself was represented on the star-map in the form of a bird seated on a high-perch. The summer solstice not only marked the longest day of the year but also the time that the sun was at its highest in the skies. In the section on the Arrow, I proposed that the bird seated on a high perch represented the solar-bird at the highest point of its annual ascent in to the heavens.The Lion has a number of inter-related themes woven into its symbolic nature. As king of the beasts he can naturally represent the king; as a ferocious predatory beast he can also symbolise war and death – the Lion's astrological omens mostly concern the vagaries of war and the occurrence of natural disasters such as famine; and as a seasonal symbol he represents the heat of high summer – his radiant mane being a simple metaphor for the overbearing rays of the summertime sun.

The goddess of war is also portrayed among the summertime stars in the form of the Bow-constellation. Together with her sacred Lion, she marks the summer as the season of war, when campaigns commenced in the spring finally come to fruition. She grants glory and victory to her royal favourites who are represented in the heavens by the King Star, which stands at the Lion's breast.—

A NYÁRI NAPFORDULÓS IDŐSZAK

A szimbólumok következő különálló csoportját a nyár folyamán felkelő csillagképek alkotják. Ezek a csillagok a forró, száraz évszakot jelölik, amelyet Mezopotámiában – ellentétben Európa enyhébb éghajlatával – a halál időszakának tekintenek. Ebben az időszakban a földeket aszály és járványok sújtják, és még maga a természet is meddővé válik – az életadó esőzések elmaradnak, a folyók vízszintje csökken, a termésnek vége, és a perzselő nyári nap alatt minden növényzet visszahal.

Ahogy a nap közeledett hatalma csúcsához, Dumuzi vészjósló álmokat látott saját haláláról. Előérzései a nyári napforduló idején valóra váltak, és a temetési szertartásokat jajgatás és siránkozás közepette a 4. hónapban, közvetlenül a napforduló után végezték el. Ahogy Dumuzi végigjárta a holtak útját, magával vitte a világok bánatát az árnyak földjére.

A halottaknak szentelt szertartások uralták az 5. hónapot is, amely a nyár végére esett. Ebben az időszakban, amikor az élet és a halál közötti fátyol a legvékonyabb volt, ünnepelték a nagy brazíri fesztivált. Ez a fesztivál az ősökre emlékezett, akiket évente meghívtak az élők világába, hogy a leszármazottaik otthonában lakomát tartsanak. A szertartások során fáklyákat és parazsat gyújtottak, hogy az ősök eltávozott szellemeit visszavezessék az alvilág sötétségéből. A nyári napforduló idején felkelő csillagok így a halál, a háború és a világok közötti utazás képeihez illeszkednek.A kígyó a halál és az alvilág egyik elsődleges szimbóluma. Görög megfelelőjéhez, a hidrához hasonlóan a babiloni kígyó is az égben állt, hogy az alvilág bejáratát őrizze. Ezt a bejáratot használta Dumuzi az alvilágba vezető úton, és ez lenne a leglogikusabb útvonal az ősök szellemei számára is, amikor a nyár végén ünnepelt nagy ősök ünnepén visszatérnek a földre. A babiloni hagyományban a kígyót Ningišzida, az "alvilág ura" számára szentnek tartották, és amikor magát a halált elképzelték, úgy gondolták, hogy annak egy kígyó arca van. A Kígyó csillagkép rosszindulatú természete túlságosan is nyilvánvaló az asztrológiai előjelekben, ahol megjelenése éhínséget, pestist és dögvészeket jelez előre. Az is lehetséges, hogy a Kígyó másodlagos szezonális szerepet tölt be, mint a nyári szárazság szimbóluma. Ennek a funkciónak a legvilágosabb kifejeződése a görög mítoszokban található, ahol a Kígyó Hydra nevű megfelelője szó szerint "vízkígyóként" ismert. A görög mítoszokban a hidrát úgy ábrázolták, mint aki a földalatti vizeket korlátozza, és ezáltal a források kiszáradását és a folyók vízszintjének csökkenését okozza.

A Rákot a görög és római hagyományokban az alvilág bejáratához is szorosan társították. Ugyanezt sugallják a babiloni hagyományok is, ahol egyes mágikus szövegek még arról is beszélnek, hogy a Rák hatását olyan rítusokban használják, amelyek célja a szellemek feltámasztása az alvilágból és a halottaknak való felajánlás. A Rákról szóló fejezetben azt javaslom, hogy végső soron ezeket a túlvilági vonásokat, valamint a folyókkal való erős kapcsolatát a régebbi Kígyó csillagképtől örökölte.

Az alvilági témák a Nagy Ikrek és kisebbik megfelelőjük, a Kis Ikrek formájában folytatódnak, akiket a csillagtérképen teljes fegyverzetű harcosokként ábrázolnak. Különösen a Nagy Ikrek, mindkettő szorosan kapcsolódik Nergalhoz, az alvilág királyához, és egyikükről ismert, hogy oda-vissza utazik a holtak birodalma és a felső világok között. A Nagy Ikrek szimbolikus funkciója a csillagnaptárban az volt, hogy őrizzék a nyári bejáratot a holtak birodalmába, amely a Kígyó és a Rák térségében található.

A világok közötti utazás témája folytatódik Anu Igazi Pásztorának és kísérő állatszimbólumának, a Kakasnak a történetében, akik mindketten az istenek hírnökeit képviselik. Isteni feladatuk az volt, hogy az istenek üzeneteit eljuttassák minden birodalom lakóihoz, ami szükségessé tette a világok közötti utazást. Az általuk közvetített üzenetek között szerepelt volna az istenek döntése Dumuzi és a többi haldokló isten sorsáról, akik most az alvilág felé tartanak. Az Igazi Pásztor, mint "az, akit lecsapott a buzogány", maga is végigjárta a holtak hosszú útját.

Magát a nyári napfordulót a csillagtérképen egy magasan ülő madár formájában ábrázolták. A nyári napforduló nemcsak az év leghosszabb napját jelezte, hanem azt is, amikor a Nap a legmagasabb pontján állt az égen. A Nyílról szóló fejezetben azt javasoltam, hogy a magasan ülő madár a napmadarat ábrázolja az égbe való éves felemelkedésének legmagasabb pontján.Az Oroszlán szimbolikus természetébe számos, egymással összefüggő téma van beleszőve. Az állatok királyaként természetesen a királyt is jelképezheti; kegyetlen ragadozó vadállatként a háborút és a halált is szimbolizálhatja - az Oroszlán asztrológiai előjelei leginkább a háború szeszélyeivel és az olyan természeti katasztrófák bekövetkeztével kapcsolatosak, mint az éhínség; és mint évszakos szimbólum a nyári forróságot képviseli - ragyogó sörénye egyszerű metaforája a nyári nap túláradó sugarainak.

A háború istennőjét a nyári csillagok között is ábrázolják az Íj csillagkép formájában. Szent Oroszlánjával együtt a nyarat a háború évszakaként jelöli, amikor a tavasszal megkezdett hadjáratok végre gyümölcsözővé válnak. Dicsőséget és győzelmet ad királyi kegyeltjeinek, akiket az égen az Oroszlán mellén álló Királycsillag képvisel.

THE CRAB

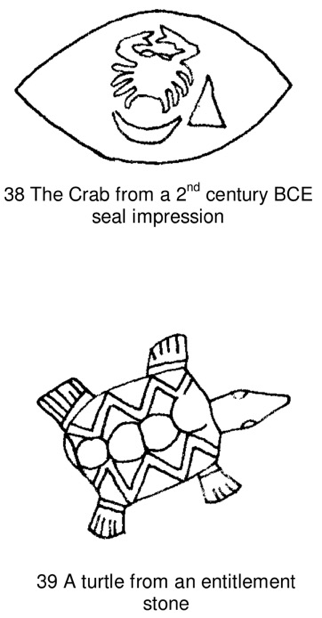

The Crab is described in a 1st millennium astrology text as having a number of stars on its sides, and containing within its centre a group of stars that are 'pressed together' – these stars are none other than the open cluster known in Greek star-lore as the Manger or Beehive. Like the Greek figure of Cancer, its latter-day namesake, the Babylonian Crab is set astride the ecliptic with its claws pointing towards the Lion.

Strangely enough there are no known depictions of a crab on any entitlement stones kudurrus], a circumstance that has led some commentators to suggest that it may be represented on these monuments by the figure of a turtle. This is, in fact, very plausible as the Crab's name can be written as Kušu, a 'water creature', which according to the lexicon can refer to a crab as well as a snapping turtle. The turtle gives every impression of being an important symbol on entitlement stones. It commonly occurs as an individual symbol, and is occasionally combined with the Goatfish. These two symbols, as well as the Ram-headed staff, which is also commonly found in combination with the Goatfish (see fig 69), are all attributed to the wise god Enki.

As the Goatfish and Ram-headed staff undoubtedly represent Capricorn and Aries, it is therefore very likely that the turtle represents Cancer – the three symbols then have an added significance in that they each mark one of the equinoxes or solstices. In the era when the MulApin was composed the Crab occupied the most northerly section of the ecliptic, where the sun, moon, and planets reached their most northerly positions. This fact probably informs its description in Mul-Apin where the constellation is called the 'seat of Anu'. The god Anu, who is literally the god of 'heaven', rules the highest and most remote of the three superimposed heavens found in Babylonian cosmology, it is thus fitting that he should rule the highest sector of the ecliptic. Perhaps for the same reason the special station of Jupiter, the 'king of the planets', is traditionally stationed between the Lion and the Crab, an association that has survived into modern times where his astrological exaltation is located in Cancer. As a creature of the waters, the Crab is used in astrological omens to predict the coming floods. The fundamentals of the scheme are expressed in binary form: 'If the stars of the Crab scintillate: high floods will come'. 'If the stars of the Crab are faint: high floods will not come'. This basic scheme is developed further in the Great Star List where the front stars of the Crab specifically represent the waters of the Tigris, and its rear stars are used to foretell the water levels of the Euphrates.

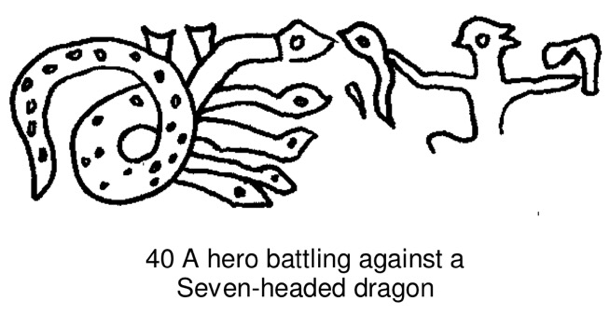

The association of the Crab with rivers is so strong that the following omen is understood to refer to the Crab even though it isn't explicitly mentioned: 'If the moon is surrounded by a river: there will be great floods and cloudbursts' – the Crab stands in the halo of the moon. Reflecting the same symbolism, late astrology texts sometimes refer to the Crab simply as 'the Waters' (A-meš).In Greek star-lore, the origins of the Crab as a celestial figure can be found among the Labours of Hercules. For his second Labour, Hercules is set the task of defeating the monstrous Hydra, a multiple-headed serpent that was terrorising the swamplands around the town of Lerna. At the height of the combat a gigantic crab emerged from the swamp to distract the hero by nipping his foot – but to no avail, as Heracles simply crushed the hapless creature underfoot. After his victory the goddess Hera reverently placed the crab into the heavens as Cancer. It has often been thought that this episode involving the crab was inserted into the Labours by an over zealous astrologer with the aim of assimilating the 12 Labours to the 12 signs of the zodiac. However, the various elements of this myth can all be found to have striking parallels in the mythology of the Mesopotamian god Ninurta. His exploits against a series of fantastic monsters called the Slain Heroes are now widely thought to provide the inspiration for Hercules' Labours. Listed among the monsters which Ninurta defeated is a seven-headed dragon, which is an obvious prototype for the Greek Hydra; the illustration (fig 40) dating to the Early Dynastic period, shows an unnamed hero severing one of the dragon's heads. Hercules' encounter with the crab is directly paralleled by another episode in Ninurta's mythology where he battles with a turtle. The story tells how Ninurta coveted the powers and symbols of civilised life (called the ME in Sumerian) for his own selfish ends. But Enki, the wise god of the Abyss, divined Ninurta's selfish intent, and fashioned a turtle to battle with him. The adversaries, locked in mortal combat, fell into a pit where the turtle kept 'gnawing Ninurta's feet with his claws'.

Although it is well beyond the scope of this book to make a comparative study of Greek and Mesopotamian myths, one significant theme emerging from this material does deserve to be mentioned – in both sets of myths the crab or turtle is either newly created or newly placed into the stars – in other words the myths detail the actual creation of Cancer as a constellation. As I have argued elsewhere, the creation of many constellations is due in large measure to the long-term effects of precession. This phenomenon slowly causes the stars to rise later and later in the calendar, thus necessitating the periodic creation of new constellations. As I hope to show in the final section, the Crab has actually inherited its principle symbolic traits from the much older figure of the Serpent.

One final aspect of the Crab's symbolism is worth exploring – it has an unmistakeable association to death, the ancestors and the path to the underworld. These associations are particularly reflected in the magical lore surrounding the Crab, which can be variously utilised to 'take hold of a ghost and let it associate with living men, to reveal the nature of men's deaths, and to offer water to a ghost'. Comparable symbolism is prominent in astrological lore where we learn that: 'If the Strange Star (Mars) comes close to the Crab: the ruler will die' and that: 'If the Crab is dark: the ghost of a wronged person (or the spirit of death) will seize the land, there will be deaths in the land'. Part of this deathly symbolism can be accounted for in calendrical terms as the Crab makes its annual appearance in the course of month 4, when the death rites of Dumuzi are celebrated. In many respects these rites form a prelude to the festival of the ancestors celebrated in month 5, in which the ancestors are temporarily invited back to the upper worlds to commune with the living – which would account for much of the magical lore mentioned above. The path that the ancestors follow to the upper worlds is located in the region of the Crab and is remembered in Greek mythology as the entrance to the underworld situated close to the Hydra's lair. Dionysus used this entrance when he attempted to bring his dead mother back from the realm of shades. And it is also remembered in Roman astrology as the 'Gates of Men', which is the route taken by the souls of babies destined to be born on earth. A further reason for associating the Crab with the underworld may be found in its Akkadian name alluttu. Although there is probably no real etymological connection, its name could easily be assimilated to the Semitic underworld goddess known as Allatum, who was later identified with Eriškigal, the great Sumerian queen of the dead. These deathly traits have undoubtedly been transferred to the Crab from the Serpent, who not only has a watery nature (see the Raven) but is also one of the principle symbols of the ancestral realm via its attribution to Ningišzida, the 'Lord of the Underworld'. Even the rebirth symbolism associated with the Crab is found in the lore of the Serpent – as the bašmu-serpent is literally the 'serpent with a womb'. To return to Hercules' Labour, we can now understand the essential action of the myth – the slaying of the Hydra and the creation of the Cancer – as a calendrical reform of the stars, which reflected the ongoing effects of precession. The ancient constellation of the Serpent had slipped back in the calendar to the point at which it no longer rose in its appropriate season and had consequently been 'killed off' and replaced by the Crab, which now embodied the symbolic traits previously associated with the Serpent.

—

A RÁK

A Rákot egy 1. évezredbeli asztrológiai szöveg úgy írja le, hogy oldalain számos csillag található, és a középpontjában egy "összepréselt" csillagcsoportot tartalmaz - ezek a csillagok nem mások, mint a görög csillagászatban Jászol vagy Méhkas néven ismert nyílt csillaghalmaz. A Rák görög alakjához, a mai névadójához hasonlóan a babiloni Rák is az ekliptikán helyezkedik el, karmai az Oroszlán felé mutatnak.

Furcsa módon a kudurru köveken nincs ismert rák ábrázolás, ami egyes kommentátorok szerint arra enged következtetni, hogy a rákot egy teknősbéka alakja ábrázolja ezeken az emlékműveken. Ez valójában nagyon is hihető, mivel a Rák neve Kušu, 'vízi lény' szóval írható, ami a lexikon szerint rákra és csattogó teknősre egyaránt utalhat. A teknős minden jel szerint fontos szimbólum a jogosultsági köveken. Általában önálló szimbólumként fordul elő, és alkalmanként a kecskehallal kombinálják. Ezt a két szimbólumot, valamint a kosfejű botot, amely szintén gyakran fordul elő a kecskehallal kombinálva (lásd a 69. ábrát), mind a bölcs Enki istennek tulajdonítják.

Mivel a Kecskehal és a Kosfejű bot kétségtelenül a Bakot és a Kos-t jelképezi, ezért nagyon valószínű, hogy a teknős a Rákot - a három szimbólumnak további jelentősége van, mivel mindegyik a napéjegyenlőségek vagy napfordulók egyikét jelöli. Abban a korban, amikor a MulApin keletkezett, a Rák az ekliptika legészakibb szakaszát foglalta el, ahol a Nap, a Hold és a bolygók a legészakibb helyzetüket érték el. Valószínűleg ez a tény határozza meg a Mul-Apinban található leírását, ahol a csillagképet "Anu székhelyének" nevezik. Anu isten, aki szó szerint az "ég" istene, a babiloni kozmológiában található három egymásra helyezett égbolt közül a legmagasabbat és legtávolabbiat uralja, ezért helyénvaló, hogy az ekliptika legmagasabb szektorát uralja. Talán ugyanezen okból a Jupiter, a "bolygók királya" különleges állomása hagyományosan az Oroszlán és a Rák között helyezkedik el, és ez a kapcsolat a modern időkben is fennmaradt, ahol asztrológiai kiemelkedése a Rákban található. Mivel a Rák a vizek teremtménye, az asztrológiai ómenekben a közelgő árvizek előrejelzésére használják. A séma alapjai bináris formában vannak kifejezve: "Ha a Rák csillagai szikráznak: nagy árvizek jönnek". "Ha a Rák csillagai halványak: nem jönnek nagy árvizek". Ezt az alapsémát továbbfejlesztik a Nagy Csillagjegyzékben, ahol a Rák első csillagai kifejezetten a Tigris vizét jelképezik, a hátsó csillagai pedig az Eufrátesz vízszintjét jelzik előre.

A Ráknak a folyókkal való kapcsolata olyan erős, hogy a következő ómen a Rákra vonatkozik, még ha nem is említi kifejezetten: "Ha a Holdat folyó veszi körül: nagy áradások és felhőszakadások lesznek" - a Rák a Hold glóriájában áll. Ugyanezt a szimbolikát tükrözve a kései asztrológiai szövegek néha egyszerűen "a vizek" (A-meš) néven említik a Rákot.

A görög csillagászatban a Rák mint égi alak eredete Herkules munkái között található. Második Munkája során Herkules azt a feladatot kapja, hogy legyőzze a szörnyűséges hidrát, egy többfejű kígyót, amely a Lerna városa körüli mocsárvidéket rettegésben tartotta. A harc csúcspontján egy óriási rák bukkant elő a mocsárból, hogy megzavarja a hőst azzal, hogy megharapdálja a lábát – de hiába, Héraklész egyszerűen szétzúzta a szerencsétlen teremtményt a lába alatt. Győzelme után Héra istennő tiszteletteljesen az égbe helyezte a rákot, mint Rákot. Gyakran gondolják, hogy ezt a rákos epizódot egy túlbuzgó asztrológus illesztette be a Munkák könyvébe azzal a céllal, hogy a 12 Munkát a 12 állatövi jegyhez hasonlítsa. E mítosz különböző elemei azonban mind feltűnő párhuzamot mutatnak a mezopotámiai Ninurta isten mitológiájában. Az ő hőstettei egy sor fantasztikus szörnyeteggel szemben, amelyeket a Megölt Hősöknek neveznek, ma már széles körben úgy tartják, hogy ezek adták az ihletet Herkules Munkáihoz. A Ninurta által legyőzött szörnyek között szerepel egy hétfejű sárkány, amely nyilvánvalóan a görög hidra prototípusa; a kora dinasztikus korból származó illusztráció (40. ábra) egy meg nem nevezett hőst ábrázol, amint levágja a sárkány egyik fejét. Herkules találkozása a rákkal közvetlenül párhuzamba állítható Ninurta mitológiájának egy másik epizódjával, amelyben egy teknőssel küzd meg. A történet arról szól, hogy Ninurta saját önző céljai érdekében megkívánta a civilizált élet hatalmát és szimbólumait (amelyeket sumérul ME-nek neveztek). Enki, a mélység bölcs istene azonban megsejtette Ninurta önző szándékát, és egy teknőst formált, hogy harcoljon vele. Az ellenfelek halálos harcba keveredve egy gödörbe zuhantak, ahol a teknős folyamatosan "karmaival Ninurta lábát rágta".Bár a görög és mezopotámiai mítoszok összehasonlító tanulmányozása meghaladja e könyv kereteit, egy jelentős téma, amely ebből az anyagból kirajzolódik, mégis említést érdemel – mindkét mítoszban a rák vagy teknős vagy újonnan jön létre, vagy újonnan kerül a csillagok közé – más szóval a mítoszok részletezik a Rák mint csillagkép tényleges teremtését. Amint máshol már kifejtettem, más csillagképek létrejötte nagymértékben a precesszió hosszú távú hatásainak köszönhető. E jelenség hatására a csillagok lassan egyre később kelnek fel a naptárban, ami új csillagképek időszakos létrehozását teszi szükségessé. Amint remélem, az utolsó szakaszban be tudom mutatni, a Rák valójában a sokkal régebbi Kígyó alakjától örökölte alapvető szimbolikus vonásait.

A Rák szimbolikájának még egy utolsó aspektusát érdemes megvizsgálni: a Rák félreérthetetlenül kapcsolódik a halálhoz, az ősökhöz és az alvilágba vezető úthoz. Ezek az asszociációk különösen a Rákot övező mágikus hagyományokban tükröződnek, amelyek szerint a Rákot különböző módon lehet felhasználni arra, hogy "megragadjon egy szellemet, hogy az élő emberekkel társuljon, hogy felfedje az emberek halálának természetét, és hogy vizet ajánljon egy szellemnek". Hasonló szimbolizmus az asztrológiai hagyományokban is megjelenik, ahol megtudjuk, hogy: Ha a Furcsa Csillag (Mars) a Rák közelébe kerül: az uralkodó meghal", és hogy: Ha a Rák sötét: egy bántalmazott személy szelleme (vagy a halál szelleme) elragadja az országot, halálesetek lesznek az országban". E halálos szimbolika részben naptári szempontból is magyarázható, mivel a Rák évente a 4. hónap folyamán jelenik meg, amikor a Dumuzi halotti szertartásokat ünneplik. Ezek a rítusok sok tekintetben az 5. hónapban ünnepelt ősök ünnepének előjátékát képezik, amikor az ősöket ideiglenesen visszahívják a felsőbb világokba, hogy az élőkkel kommunikáljanak - ez magyarázza a fent említett mágikus hagyományok nagy részét. Az ösvény, amelyen az ősök a felső világokba jutnak, a Rák területén található, és a görög mitológiában úgy emlékeznek meg róla, mint az alvilág bejáratáról, amely a Hidra búvóhelye közelében található. Dionüszosz ezt a bejáratot használta, amikor megpróbálta visszahozni halott anyját az árnyak birodalmából. A római asztrológia az "Emberek kapujaként" is megemlékezik erről a bejáratról, amelyen a földi születésre szánt csecsemők lelkei járnak. További ok arra, hogy a Rákot az alvilággal hozzák kapcsolatba, az akkád alluttu nevéből adódik. Bár valószínűleg nincs valódi etimológiai kapcsolat, neve könnyen megfeleltethető az Allatum néven ismert sémi alvilági istennőnek, akit később Eriškigallal, a nagy sumér holtak királynőjével azonosítottak. Ezek a halálos vonások kétségtelenül a Kígyótól kerültek át a Rákba, amely nemcsak vízi természetű (lásd a Holló), hanem Ningišzida, az "alvilág urának" tulajdonítása révén az ősbirodalom egyik fő szimbóluma is. Még a Rákhoz kapcsolódó újjászületési szimbolika is megtalálható a Kígyó hagyományában - mivel a bašmu-kígyó szó szerint a "méhvel rendelkező kígyó". Visszatérve Herkules Munkájához, a mítosz lényegi cselekményét - a Hidra megölését és a Rák megteremtését - most a csillagok naptári reformjaként értelmezhetjük, amely a precesszió folyamatos hatásait tükrözi. A Kígyó ősi csillagképe a naptárban visszacsúszott arra a pontra, amikor már nem a megfelelő évszakban kelt fel, és ennek következtében "elpusztult", és helyébe a Rák lépett, amely most már megtestesítette a korábban a Kígyóhoz kapcsolódó szimbolikus vonásokat.

Gavin White könyvének interneten elérhető kivonataiban tallózva az előző jegy a (Nagy) Ikrek Mastabbagalgal, a következő jegy pedig az Oroszlán Urgula.

A fenti szövegben szerepel, hogy későbbi csillagászati szövegekben a Rák jegy neve A-MES (Vizek), melyre úgy asszociál G. White, hogy értelme egybevág az azt megelőző sorokkal. Igen ám, de MES-nek egész más jelentéseit (is) ismerjük. Továbbá a Ráknak utalni kell holtpontra. Lásd Paksi Zoltán írását Rák csillagkép.